Trial Magazine

Theme Article

Optimize e-Discovery Production

Whether you represent an individual or an entity such as a local or state government, you must know how to collect, preserve, and sort electronic data efficiently.

August 2021Despite being available in some format for almost two decades, the adoption of e-discovery practices in the legal profession continues to lag behind technological advances. This is problematic given the enormity of the digital universe.1

When requests for production reach your desk, you must have a plan ready for how to collect, preserve, and sort through the myriad of data sources your client may possess. Regardless of your chosen e-discovery platform, you need to follow several key steps throughout the document review process. This is especially true when you are representing multiple plaintiffs in a mass action or local and state governments—for example, in environmental and chemical contamination litigation. In these cases, e-discovery production is very complicated—it involves many different data sources that you and your team will need to investigate.

Charting the Unknown

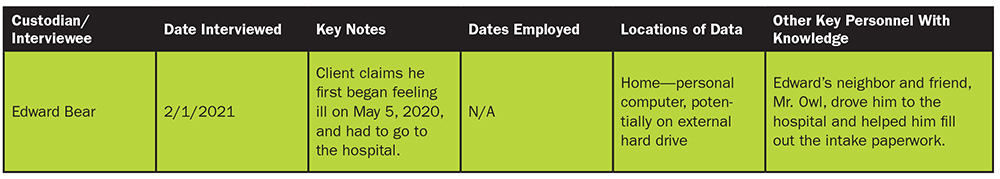

At the outset, create a plan to identify, obtain, process, and analyze the relevant information in your client’s possession. As you discuss the claims with your client, identify the main issues, the key players—any people or entities involved within your client’s organization—and the technologies they used. It is imperative to establish quick contact with those in the organization most familiar with both the technology and legal issues of the case, such as in-house counsel and IT departments. Interview these people to collect and preserve all data related to the case. Through this process, you will learn the identity and knowledge level of others who may have relevant data, including third parties, consultants, and other client representatives. This process also ensures compliance with preservation requirements consistent with court orders and applicable ethics guidelines.2

Data mapping. Identifying the various technologies your client used is referred to as data mapping—creating a comprehensive outline of an individual’s or organization’s potential data (evidentiary) sources. Data mapping is essential to understanding the scale, scope, and location of the information you seek while also ensuring that information is not overlooked or lost. Data mapping tells you where data is stored and for how long each source is typically preserved. Obtain the client’s document retention policy as part of your mapping process, noting the relevant time periods for how long each type of data is preserved. For instance, an entity may have a 30-day overwrite period for video before it is deleted.

Keep a log of when the search was performed, who performed it, what was searched, how it was searched, and what results the search returned.

To start data mapping, determine the technology that the client used during the relevant time period, including computer programs, networks, data storage (portable, local, or cloud), cell phones, social media, intranet and internet web pages, digital watches, video, vehicle black boxes, and so on.

Remember, when the plaintiff is an entity, such as a local or state government, you must work with its employees and IT personnel—they will assist you in identifying, preserving, and collecting information from all potential sources. When you have completed the data map, prepare or modify litigation hold notifications to ensure all sources are adequately described for preserving the relevant data.

Develop search terms. Design appropriate search terms or parameters to use when searching the electronically stored information (ESI) in a client’s possession to capture as much relevant data as possible. Use your understanding of the case and its main issues, as cited in the complaint and any discovery requests you have served, to formulate search terms. Broader search terms may capture more potentially relevant information in the initial electronic (automated) or manual search for data. For the manual search, the client’s IT personnel and primary custodians typically use search terms to locate data on their personal computers, including data saved on their home screen or in personal folders.

Due to the associated expense of processing and storing large quantities of ESI, consider testing the viability of the proposed search terms in a limited setting first. Use the initial list of search terms to “test search” the client’s email system to determine the applicability and number of “hits” that the proposed terms return. Based on the results of those test searches, consider narrowing the terms or confine future searches by date or other parameters.

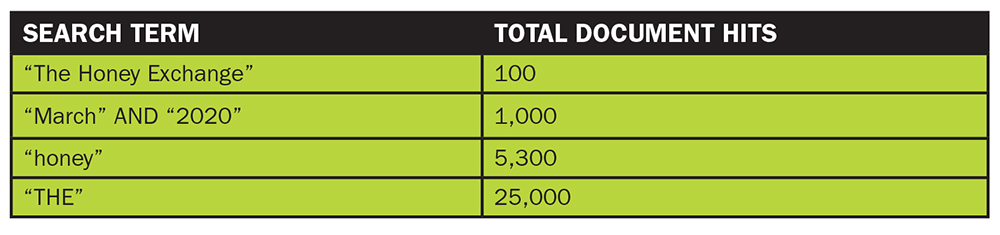

For example, suppose the client, Edward Bear, sues Eeyore Blue and his company, The Honey Exchange (THE), over 100 jars of contaminated honey he purchased in March 2020. You have decided to try various search terms to locate relevant documents within Edward’s possession. (See a sample “hit report” for these search terms below.)

Your search terms should endeavor to be overinclusive rather than underinclusive so you do not fail to produce important or wholly relevant documents. However, the wrong search term can result in a dramatically large number of documents that likely contain irrelevant, useless, or “false” information—known as “false hits.” In the example search, “THE,” the acronym for The Honey Exchange, would pull documents referring to The Honey Exchange as well as every document with “the” in it.

Retain a copy of the hit report—it will be useful to share with the opposing party to negotiate discovery parameters during the meet-and-confer process or as required by the court.

Documenting the Journey

Do not underestimate the importance of documenting the results of your data collection efforts and related ESI searches. This step avoids duplication of efforts and also demonstrates due diligence and reasonable actions in completing the data collection process consistent with all related legal obligations.

In addition to the hit report, keep a record of each witness and records custodian you interview in the case, starting with key witnesses and then branching out as appropriate. For example, in a wildfire case, consider interviewing the fire chief and any first responders to ensure that you have preserved and collected all physical and electronic records (such as manuals or business logs); photos or texts related to the fire on their personal or work-issued phones; alerts sent to the community on public websites; and any related internal process data, including emails or texts to their team.

Additionally, create a standardized interview checklist to ensure all the appropriate bases with each witness/custodian have been covered. The checklist should

- confirm that the witness/custodian received an appropriate litigation hold notice

- explore all of the possible locations where pertinent information may be stored—whether hard copy or electronic and portable, local, or in the cloud—and any proprietary software programs

- discuss personal and professional retention practices for various information sources such as text messages, voicemails, emails, and documents

- identify other potential witnesses and the location of any other relevant information.

As you document the results, ask witnesses/custodians:

- Did you collect all available data?

- Did you check for laptops, external hard drives, cell phones, and the like?

- If so, record every location where you collected and searched for relevant information.

If the client has IT personnel, have that staff help you identify network drive locations, access proprietary software systems, develop search parameters, and confirm that relevant information is not being unintentionally destroyed. This last item is especially important because it can lead to a spoliation of evidence claim. Always request copies of any retention policies your client follows, and inquire how long any computer and phone-related information is stored before it automatically deletes.

To avoid possible spoliation claims, address some related concerns upfront. First, capture any phone, video, social media, and intranet data. Also, consider whether any temporary employees, former employees, or third-party witnesses who are not covered by or privy to a litigation hold may have relevant information. If so, take all necessary steps to preserve that information too.

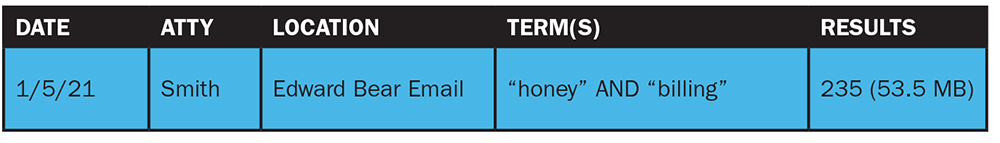

For every custodian, record what devices were searched, how they were searched, and the resulting ESI collected. Keep a log that records when the search was performed, who performed it, what was searched, how it was searched (including the specific search parameters), and what results the search returned. For example, if attorney June Smith searched Edward Bear’s email account for all documents referencing “honey” and “billing,” and the search returned 235 emails or 53.5 MB of data, you need to log that search. (See the log below.)

When discovery disputes arise, this log will help in the meet-and-confer process with opposing counsel. The efforts demonstrate the due diligence used in collecting responsive documents from the client and, at the same time, set the expectation for the defense to follow in their corresponding collection and production. The collection log also may serve as the information source for manual date entry when ESI metadata must be provided to opposing counsel.

Sorting & Reviewing ESI

After collecting the relevant ESI, upload it into an e-discovery review platform to assess it for relevance, confidentiality, and privilege.

Organize what you have. As an initial matter, process the data to eliminate any duplicates (de-duplication) and identify email chains and “junk” emails. Flagging email chains in the initial sorting ensures the related documents are uniformly coded. Flagging junk emails, such as advertisements from Groupon or newsletters from a yoga studio, effectively culls this data from the review set to avoid wasting valuable review time on irrelevant material. If a significant number of junk emails are found, consider sharing this information during meet and confers with opposing counsel to explain known false hits with search terms.

When the data sorting is completed, organize the remaining data to be reviewed. Sort data into folders of privileged/potentially privileged documents, junk documents, “hot docs” (documents that may be useful to the opposing party), key witnesses, and main issues—all of which makes data more user-friendly and readily accessible.

Try to reach an agreement with opposing counsel before conducting these initial searches about what the parties need to log and what they do not (for example, no logging of core privileged materials developed after the commencement of litigation, such as correspondence with counsel) and whether irrelevant data captured by initial searches should also be produced or simply sorted out (such as junk emails).

For example, in documents collected from Edward Bear, newsletters and advertisements from other honey vendors may arise. Such nonprivileged junk documents can either be classified as responsive or excluded from production, depending on the facts of the case. Often, these documents are produced because they may tangentially relate to the case or the parties’ knowledge about the core litigation at issue, or they may be used to show the producing party’s inclination to provide even tangential materials to the opposing party.

For example, newsletters with advertisements about the quality of honey, such as “top quality” and “free of contaminants,” may be used to show the diligence of the company selling the honey. Other junk emails may simply be personal correspondence to an individual nicknamed “Honey” that can be excluded.

Remember to search the metadata, such as the file name and file path, not just the contents of the documents. In the honey case example, you may have a folder on your network drive called “Honey Lawsuit,” which you have copied and uploaded to your review platform. The documents contained in this folder have a file path of C://personal/Honey Lawsuit. The folder contains Edward Bear’s ER bill from going to the hospital after eating the bad honey he purchased from Eeyore Blue. Without the information from the file path and folder name, the possibility exists of missing this key document if the document does not contain one of your search terms.

Segregate privileged documents. Search the data and separate potentially privileged information using attorney and law firm names as well as any consultant names. Use references to the underlying litigation as your search terms. As these materials are identified, put them in a separate folder for privilege review. Note, however, that there may be false hits, depending on the search terms used. Correspondence with an attorney regarding other lawsuits for the contaminated product may be excluded, or correspondence related to the instant case with internal counsel about filing the lawsuit may or may not be excluded, depending on your agreement with opposing counsel.

In the honey case example, a search for “Smith” to identify any privileged materials from attorney June Smith reveals that “Smith’s” is the name of another local honey supplier. Once these documents have been confirmed as not privileged, exclude such data from the production, depending on any agreement with opposing counsel to exclude nonrelevant data if it is not integral to the case. But always keep the search and related data in a separate folder.

Start reviewing. After removing duplicate data, potentially privileged data (for separate review), and junk data, the remaining documents need to be reviewed for relevance and confidentiality and then ultimately produced. Sort the data by author (creator) and recipient, if applicable. This allows for the categorization of the potential relevance of the data to then rank its priority and significance in terms of the review process and case development.

Sorting documents by author allows you to quickly assess the particular documents associated with each witness, making deposition preparation less of a guessing game and more comprehensive. It also hastens the identification of potential hot docs.

In addition, documents that contain information relating to the primary subject matter but that are between parties not entitled to privilege designations or otherwise designated as key players can be produced without the more detailed review of their contents that other documents will require. For example, inquiries regarding the quality of honey from other parties, such as the Honey Control Board, could be released without further review, as it is not a privileged party.

Sorting through the relevant but nonprivileged documents provides crucial underlying information about the case, which is invaluable to organizing and developing the case story and theme. Start by reviewing those documents associated with your high-priority search terms (the main issues in case). For instance, review medical records regarding the incident first as they will contain highly relevant information related to your cause of action and damages. Record significant factual findings and sources of data in a spreadsheet or table. (For an example, see below.)

Make a list of important fact witnesses, companies, experts, and consultants; identify main issues and associated supporting facts; and note or tag issues important to the case using the review platform. Also include any facts and documents that do not support the case; this allows the litigation team to identify and address any weaknesses early, such as a statute of limitations and other potential defenses.

While reviewing the data, also track the names, firms, addresses, and email addresses of every attorney involved in the matter, as well as any expert consultants whose work may be entitled to a privilege designation. Track the key players in the underlying dispute by name, job title, role, and email address, and note any involvement they had in any privileged or potentially privileged matters. This information will help you to easily prepare a clean and thorough privilege log at the conclusion of the review. It also confirms the propriety of the review.

Documenting and organizing your e-discovery collection and review process is crucial to developing your case and meeting production obligations. While the technological aspects of the process are admittedly daunting at first, your comfort level will grow with practice—and your document productions will be more efficient and manageable.

Staci J. Olsen is senior counsel of electronic discovery at Baron & Budd in Dallas and can be reached at solsen@baronbudd.com.

Notes

- insideBIGDATA, The Exponential Growth of Data, Feb. 16, 2017, https://tinyurl.com/hur9c75n.

- See, e.g., Model R. Prof’l Conduct 1.1, 3.3, 3.4.